I decided to publish my write-ups from my comprehensive exam reading fields. I am publishing them *as is.* Thus they represent my thoughts as a new PhD student. They were written between September 2011 and July 2012. The full collection is accessible here.

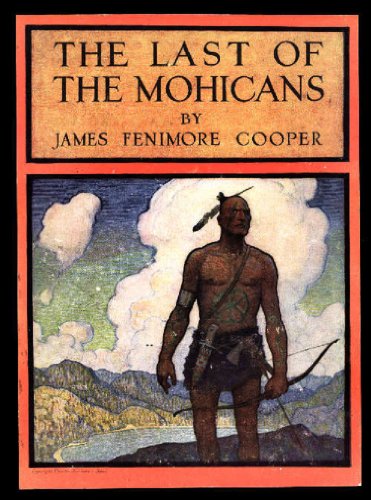

The Last of the Mohicans; A Narrative of 1757

James Fenimore Cooper

- James Fenimore Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757 (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983).

The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757 is the second novel in James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales series. The series features the white pioneer, Nathaniel “Natty” Bumppo, who is also known as Leatherstocking and as Hawkeye. Last of the Mohicans takes place in Glen Falls, New York during the French and Indian War, and is based upon actual occurrences surrounding Colonel George Munro (or Monro) and his command of Fort William Henry. The novel starts with a group of reinforcements that are traveling to Fort William Henry. In this group are Munro’s two daughters, Cora and Alice. They are lead by a Huron scout, Magua, who, unbeknownst to them, is planning to lead them into a surprise attack. However, his plan is thwarted by the entrance of Hawkeye, Chingachgook, the chief of the Mohicans, and Uncas, Chingachgook’s son and the subject of the novel’s title. The main substance of the novel is based around the jostling back and forth between the French, led by Marquis de Montcalm, and the Hurons, represented by Magua, and the British, characterized by the Munros, Major Heyward, and General Webb. Hawkeye, Chingachgook, and Uncas align themselves with the British. The novel concludes with the deaths of Uncas and Cora. Uncas’ death symbolizes the approaching end, not only of the Mohicans, but of all Native Americans and the foreseeable conquering of the land by the supremacy of the White Man. Cooper’s novels lent a great deal to the jumpstarting of the Western fiction genre, and his treatment and characterization of the frontier greatly influenced the genre in later decades.

Wilderness in The Last of the Mohicans often plays an ominous role. It is described as a place of “toils and dangers.” Magua and other Hurons, the more savage of the Indians, are able to almost melt into the forest and mountains; for the wilderness is both the creator and the protector of savageness. Those items of nature that are pleasing and pleasant, such as the flower, are suggested to not really belong to the wilderness, but to rather be misplaced. Their true home is amidst civilization where its beauty and softness can be truly appreciated. The bulk of Cooper’s description and characterization in The Last of the Mohicans revolves around the Native Americans. Cooper is especially taken with the concept of the noble savage, the gentlemen of the wilderness, which is embodied by Chingachgook and Uncas. Uncas is said to emanate “romantic wildness.” The Native Americans are described to be very wise and sensitive to their surroundings. Their intelligence is not based on book smarts, like that of the White man, but rather on experience. They are honest and hospitable. Yet, the thing that makes Chingachgook and Uncas so likeable is seemingly that they have largely adopted the thinking of their white companion, Hawkeye. However, this portrayal of the Native American is sharply contrasted throughout the book by the character of Magua and other Indians like him that are not lucky enough to have been enlightened by European companionship. Magua is described as swarthy, immoral, and malevolent. Similar to Francis Parkman’s treatment of Native Americans, Cooper also highlights their simplicity and childish attachment to finery with which they can easily be bragged. The most appalling description of the Native American occurs after the massacre. “The flow of blood might be likened to the outbreaking of a torrent,” Cooper writes, “and as the natives became heated and maddened by the sight, many among them even kneeled to the earth, and drank freely, exultingly, hellishly, of the crimson tide.” (176) This depiction is one of intense savagery that lowers the Indian to the bottom of humanity’s ladder. The true curse of the Native American is that of their skin color. Cooper places a great deal of emphasis on the noble traits that are inherent amongst white people. The Indian, despite trying to learn the white man’s ways, will never be able to overcome the disabilities of their race.

Cooper’s description of Natty Bumppo is one that very closely mirrors the romanticized characterization of the frontiersman in Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis. Bumppo is a man that is free from the constraints and enticements of civilization, and thus, being in such proximity to savagery, is able to acquire some of the untainted qualities of the uncivilized Indian. Because Bumppo is familiar with some of the customs of the civilized world, he is able to take the wilderness and make it his own, rather than falling victim to it. Bumpo is an individual who is able to start once again at the beginning stage of Turner’s civilization process. How much was Turner influenced by Cooper and other writer’s works? Was Turner only restating an idea that had been around for decades in a more academic tone?

Hi Jessica, thank you for the generosity of continuing to share these insights. You may be amused (and probably already know?) by Mark Twain’s takedown of Cooper http://twain.lib.virginia.edu/projects/rissetto/offense.html

Pat Nunnally (@RiverLifeUMN)

On Thu, Apr 11, 2019 at 1:55 PM Historical DeWitticisms wrote:

> Jessica M. DeWitt posted: “I decided to publish my write-ups from my > comprehensive exam reading fields. I am publishing them *as is.* Thus they > represent my thoughts as a new PhD student. They were written between > September 2011 and July 2012. The full collection is accessible here” >

LikeLike

Love it!

LikeLike